Tuesday, 20 November 2012

Did the Indian Capital Controls Work as a Tool of Macroeconomic Policy?

At the main page for this paper, you will find all the materials: a video presentation, PDF paper, link into the journal, a compact summary on voxEU.

Friday, 16 November 2012

Growing pains

Indian Express, 16th November 2012

Clarify policy and ease bottlenecks to spur investment

Preventing India's growth slowdown is a difficult but not impossible task. The government needs to follow a two-pronged strategy to put India back on a high-growth path. On the one hand, it must focus on putting stalled projects back on track. On the other hand, it must put in place policy frameworks for the allocation of land and natural resources, as well as for environmental standards and the rule of law.

Episodes like the 2G spectrum sale and the coal block allocation issue demonstrate that the lack of a clear framework can seriously disrupt investment and growth. Though there are no easy answers to these questions, arriving at policy frameworks through research, public consultation and discussions among stakeholders, and implementing the rule of law, should make them more tractable than they are today.

One somewhat simple way to address growth slowdown in the short run may be through fiscal and monetary policies. But in India, macroeconomic policy choices, even in the short run, are going to be very difficult. The latest data on output and prices confirm the stagflation that has been on its way. We now see growth slipping below 5 per cent, even as consumer price inflation reaches 9.75 per cent. This is almost the reverse combination of what India witnessed a few years ago at the peak of the business cycle.

As output growth slipped in September 2012, with the IIP data showing an actual contraction in economic activity, consumer price inflation continued to rise, hitting almost double digits. The trade data released also showed a higher trade deficit. Stagflation is a much more difficult problem than overheating, which happens when prices and output are both rising, and which we saw in 2006 and 2007. That is when fiscal and monetary policy both need to be contractionary. Tackling stagflation is also more difficult than facing a recession, when fiscal and monetary policies both need to be expansionary. When faced with stagflation, no standard recipes work. Contractionary fiscal policy would mean raising tax rates, something that would hurt investment further. Easing monetary policy would mean cutting interest rates, something that would make inflation worse. The experience of other countries like the US, which has seen stagflation in the past, suggests that simple solutions can only worsen economic conditions.

Standard macroeconomic stabilisation policies are not the answer to India's economic problems today. One clear area of failure, which needs government action, is governance issues. These are responsible for having created an environment that has put on hold various projects and discouraged further investment. The stalling of a large number of investment projects since governance problems began, especially after 2010, have reduced investment and worsened supply constraints, particularly in infrastructure. Various bottlenecks, especially bureaucratic and judicial, are now holding back the economy as never before. The tools of macroeconomic policy are meant to address an economy operating around its full capacity output. That framework assumes that problems such as India's do not exist. India is not at its long-run, steady-state growth rate. The output gap is not caused by investment inventory cycles, which can be addressed by macro policies.

To address immediate governance issues, the government has proposed a National Investment Board (NIB) to speed up stalled projects. This could help push up output as well as bring down prices. But the environment minister, Jayanthi Natarajan, has opposed routing environmental clearances through the NIB. This brings us to the question of how the NIB will work. Can the bulk of issues on which investment is stalled be resolved without transparent policy frameworks in place?

There is no doubt that the reforms proposed by Finance Minister P. Chidambaram created optimism among investors, both foreign and domestic. But while it is true that the gloom and doom went away, it was replaced only by a very cautious optimism. Investors need to see the government take concrete steps before making investment decisions. If large projects and large sums of money continue to be stuck in governmental processes, and investment decisions keep getting postponed, it will not encourage them to invest. Not only are resources limited, an increasing number of bad assets reduces the banks' ability to lend. It is not just that companies are constrained by their capacity to incur further risk, there is a trust and governance deficit. Equally important are the worsening finances of the banking sector. The government needs to act quickly.

But if the laws that create a policy framework are not in place, there are fears that the very clearances that such a board gives could be challenged in court the very next day. Therefore, the second element of the strategy is to understand why projects were stalled and to correct the existing policy frameworks.

There will be no simple answers. In the process of economic growth, there are trade-offs between protecting the environment, forests and land rights on the one hand, and creating infrastructure, generating power, making dams, encouraging mining and other economic activity on the other. Any solution that swings to one extreme will not work. It will be very easy to stall projects if citizens who are losers in the process, or those that support them, go to court or use political pressure to stop economic activity. Any attempt to push through projects in a non-transparent or arbitrary way will not be acceptable either. There is no doubt that India will have to industrialise, but in such a way that the environment and forests are protected. It is essential to put in place the rule of law and processes to ensure that such issues do not hijack politics and economics.

Most countries face similar problems when they grow fast. As the Indian economy has grown, the stakes involved have become very high. With that, corruption in high places has become more attractive. What must be a priority is the creation of policy frameworks, for example, strategies for the sale of natural resources or public sector enterprises, through auction or otherwise, should be formulated in a transparent, consultative process, with independent research and discussions with stakeholders, where the public understands the debate and buys into the solutions.

Thursday, 15 November 2012

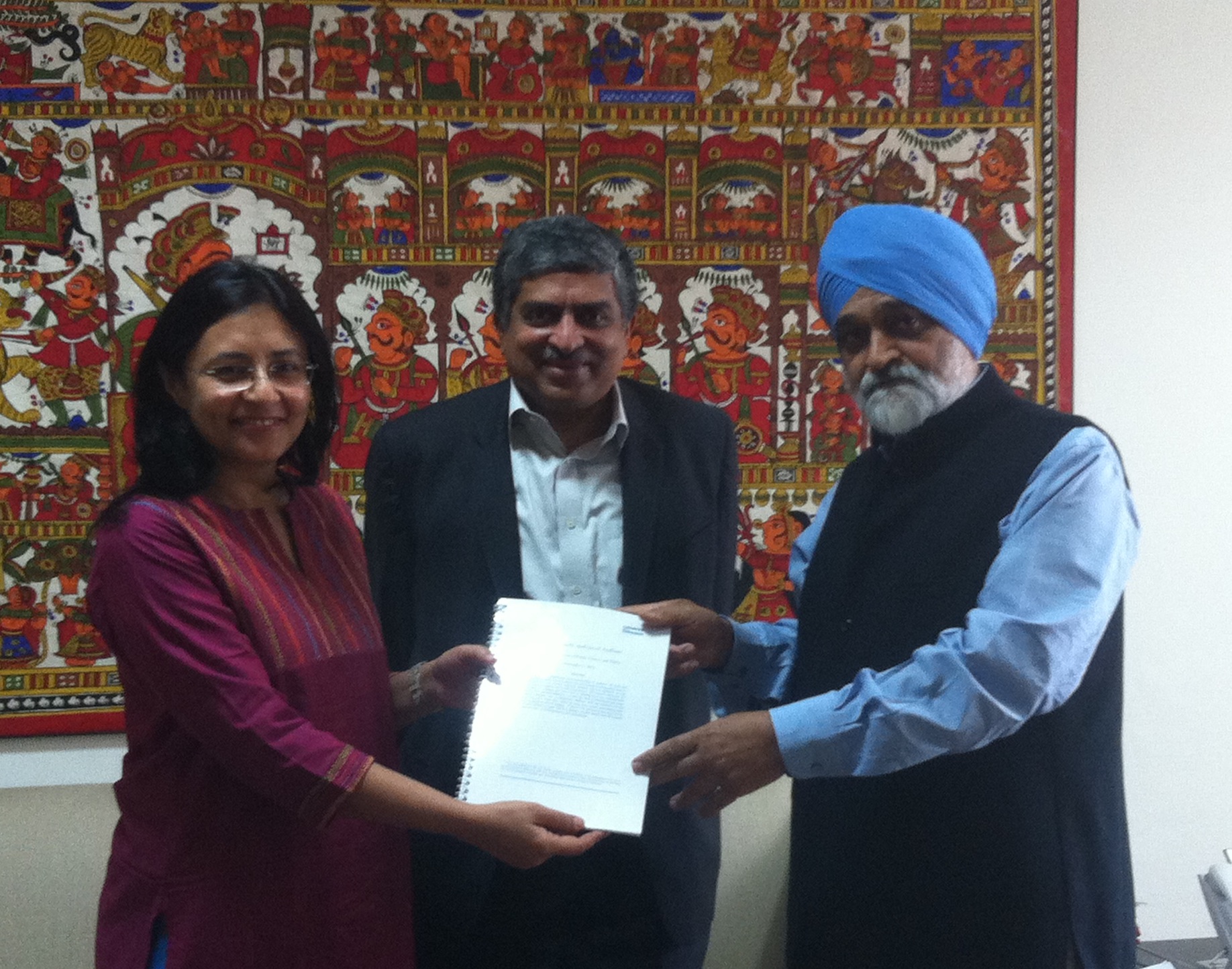

NIPFP study finds large returns from Aadhaar project

The National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP) released a study on a cost-benefit analysis of the Aadhaar programme, showing that Aadhaar can plug problems ofleakages and yield very high returns to the government.

The National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP) released a study on a cost-benefit analysis of the Aadhaar programme, showing that Aadhaar can plug problems ofleakages and yield very high returns to the government.

This study is significant in the light of the current debates on how to reduce the subsidy bill.

The study finds that substantial benefits would accrue to the government by integrating Aadhaar with schemes such as PDS, MNREGS, fertiliser and LPG subsidies, as well as certain housing, education and health programmes. Even after taking all costs into account, and making modest assumptions about leakages, of about 7-12 percent of the value of the transfer/subsidy, the study finds that the Aadhaar project would yield an internal rate of return of 52.85 percent to the government.

Integrating Aadhaar with government welfare schemes will improve identification and authentication. Hence, the leakages due to duplicates and 'ghost beneficiaries' can be tackled. Plausible estimates about such leakages are available mainly for MNREGS and PDS programmes in government reports and the academic literature. Using these estimates as benchmarks, for the components of the leakages that Aadhaar can directly address, the NIPFP study extends the analysis to include other government schemes where transfer to beneficiaries takes place. A reduction in leakages is considered a benefit to the government since the funds can be saved and used for other purposes.

For the PDS, the benefit accruing due to integration with Aadhaar is assumed to be in terms of reduction in leakages in the delivery of foodgrains (rice and wheat) and kerosene. For MNREGS, using the wage expenditure data and several social audit reports, the reduction in leakage in wage payments through muster automation and disbursement through Aadhaar-enabled bank accounts has been estimated. For fertilisers and LPG distribution, the diversion is estimated as a percentage of the government subsidy, which is assumed to be getting leaked or diverted for purposes beyond the subsidy's rationale. For other schemes, which include the Indira Awaas Yojana, Janani Suraksha Yojana, various pension schemes, scholarships, and payments made to workers under NRHM and ICDS, the leakages due to identfication errors are estimated as a percentage of the value of the transfer payment.

The costs of developing and maintaining Aadhaar, as well as integrating Aadhaar with the government schemes is computed in the study.

Thus, comparing the benefits with the costs, the NIPFP study concludes that the internal rate of return in real terms of the Aadhaar project is 52.85 percent. This analysis shows that even with modest assumptions on benefits, the Aadhaar project yields a high internal rate of return to the government.

The NIPFP study focuses on certain tangible benefits accruing to the government, and therefore does not count the benefits to the economy and the intangible benefits to the government and society. Many benefits of the program are intangible and therefore difficult to quantify. For example, by making every individual identifiable, existing government welfare schemes can become more demand-led. Beneficiaries are better empowered to hold the government accountable for their rights and entitlements, thus influencing the way these schemes can be designed and implemented. Also, with digitised, non-local information on workers seeking jobs, labour mobility and migration experience will become easier.

The study argues that if we were to add more programs and expand the scope of the analysis, and consider the intangible benefits, it is likely that the returns will be higher.

Full details of the calculations have been released on the NIPFP website. Other scholars and policy analysts can modify some assumptions and explore alternative outcomes.

Wednesday, 7 November 2012

NIPFP Macro-DSGE Workshop, 2012

Conference Program

Date: November 12, 2012

Time: 09:30 A.M.

Venue: Conference Hall, Ground Floor, New Building

National Institute of Public Finance and Policy,

18/2 Satsang Vihar Marg, Special Institutional Area,

New Delhi - 110067

View Larger Map

Governance 2.0

Indian Express, 7th November 2012

The idea of economic reform in India has largely been seen as the reduction of restrictions imposed by the government on economic activity - it must go beyond this narrow scope. The next wave of reforms needs to focus on governance. The lack of transparency in the government's functioning at present is increasingly unacceptable.

In its recent approach paper, the Financial Sector Legislative Reform Commission (FSLRC) outlined recommendations to bring about an improvement in governance, with a focus on financial sector regulation. These proposals hold lessons for the ways in which the government functions in other sectors as well.

Many government tasks can be outsourced to external agencies. This is motivated by two considerations: political independence and functional autonomy. The Election Commission should not care about pleasing the ruling party, so it should be politically independent. Tax administration should not be used by the ruling party to harass rivals and obtain election funding. Thus, tax administration should be politically independent. In finance, functions such as regulation and supervision should be immune to political pressure, much like tax administration should be distanced from politics. In addition, monetary policy should not be influenced by or subject to election cycles, which makes a case for the political independence of the RBI.

The second kind of autonomy is functional. This is rooted in problems that arise from the outdated ways in which the Indian government operates. It is difficult to construct competent and professional structures within the government, given the weaknesses of human resource processes, cumbersome procurement policies, etc. If bodies external to the government are freed from the strictures that depress its productivity, superior outcomes can be attained. Bodies outside the government can aspire to the professionalism, specialised staff capability and efficiency of the private sector once they are free to deviate from government processes.

These two reasons make a compelling case for political independence and functional autonomy in many situations. But we have to be mindful about accountability. When power is given to unelected officials working in agencies external to the government, what is the mechanism by which accountability can be ensured? Why will these officials pursue the public interest? Will they not, instead, pursue their own interests? In recent decades, we have watched agencies external to the government fail to cater to the interests of the people. They tend to do things that are convenient for existing officials, reduce the work of the agency and increase discretionary power. They also avoid taking responsibility.

It is important to consider the independence of these agencies, but it is essential that questions of accountability also be included in the discussion. A government agency is only well structured when it has the right blend of independence and accountability. Enshrining independence mechanisms in the law must go along with enshrining accountability mechanisms in the law.

The FSLRC has laid out four paths to accountability. The first is clarity of purpose. Poorly specified goals give officials a free hand to pursue their pet projects. So, laws must set down specific objectives and powers.

These goals must not be internally contradictory. For example, the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority was given the job of regulating insurance companies and of developing the market for insurance. When it supported the unhealthy sales practices of insurance companies with the sale of unit-linked insurance plans, it could claim that it was sacrificing the regulation objective in favour of the development objective. The RBI is able to argue that it failed on inflation control because it has been holding interest rates low in order to pursue other goals, such as preventing exchange rate fluctuations, obtaining low-cost financing for public debt, preventing banks from failing, etc. Each department or agency must have clarity of purpose and not suffer from inherent conflicts of interest.

The second area of concern is the rule-making process. Parliament delegates the writing of rules to regulators, an enormously powerful tool to hand unelected officials. While it is valuable to have officials with professional expertise, we should be mindful of the extent to which unelected officials can pursue their own interests. Hence, the delegation of rule-making powers must be accompanied by an elaborate array of checks and balances in the rule-making process. Regulators must be made to demonstrate that the gains to society from a proposed rule exceed the costs of complying with restrictions. Draft rules must be released to the public and specific responses must be released for every comment. There should be convenient forums for appeal, where rules are subject to judicial scrutiny.

The third area of concern is the rule of law. India's economic policy today has seen numerous failures in that respect, partly due to the socialist policies of the past. There is a need to strip regulatory agencies of arbitrary power. Laws should be known before an action is taken; laws should be applied uniformly; when a law is invoked, it should be accompanied by the rationale employed for its use; and specialised courts for appeal should be available.

The fourth element of accountability is reporting. Once an agency has been properly structured and its objectives have been clearly defined, it should be asked to report on the extent to which it has met these objectives and how it will do better in the future. For instance, a government agency set up for the specialised purpose of addressing consumer complaints in finance must document the case backlog and the extent to which its orders were upheld on appeal, survey evidence about the satisfaction of citizens who filed a complaint, and report the cost of the process as seen by individuals, the compliance cost imposed on firms, etc. Annual reports today are filled with general platitudes about the economy, and reporting must shift away from that to include specific outcomes that the agency was mandated to achieve.

This approach to improved governance emphasises transparency, consultation and rule of law. The application of this approach in the financial sector and beyond will lay the foundation for improved public administration in India.