Indian Express, 27th December 2012

Don't let bureaucracy or politics of reciprocity hold back trade with Pakistan

In a significant step towards better India-Pakistan bilateral economic relations, Pakistan is expected to operationalise the Most Favoured Nation (MFN) status to India in the next few weeks. Under this regime, Pakistan will give trade treatment to India at par with other nations, which will allow more Indian goods to be imported into Pakistan. India took the lead in giving Pakistan MFN status in 1996. India should similarly take the lead in further increasing trade in goods and services, and in the flow of capital from Pakistan.

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh initiated unilateral trade liberalisation in India in 1991. In his current tenure, he has worked towards improving the India-Pakistan relationship, despite the many conflicts that obstruct peace in the region. Combining the two elements - unilateral trade liberalisation and the objective of improved relations with Pakistan - is the next step. Instead of being held back by the bureaucracy and the politics of reciprocity in trade agreements, India must move first. India is the larger economy, and the prime minister understands the gains from trade liberalisation and from better relations with Pakistan.

The need to increase economic cooperation between the two countries as a means to build stakes in peace was reiterated in the recent Track II dialogue at the Chaophraya initiative, a forum of interaction for academics, parliamentarians and media of both countries. The need for building economic bilateral relations was emphasised, even as security issues create a trust deficit in other areas. Trade and investment across the border will help create lobbies and interest groups that would engage with each other, and put pressure on both governments to improve political relations and work towards solving other more difficult questions on Kashmir, terrorism, Afghanistan and nuclear security.

The recent agreement on the liberalised visa regime between India and Pakistan is a small step in the right direction. Granting visas for business will help facilitate trade relations. These initiatives need to be followed by measures to increase services trade. The removal of the remaining restrictions and red tape, even in areas where agreements have been signed, should be a priority.

Research suggests that India-Pakistan trade is lower than the volume of trade that takes place between countries that are so close, geographically and culturally. This is because of a large number of barriers, both tariff and non-tariff, that prevent trade. The proof that there is a demand for each other's products is demonstrated by the large amount of illegal trade that is taking place between the two countries. Since the countries are neighbours, the cost of transportation is low. However, there are restrictions on the kind of products they can import from each other. Trade for such products takes place through Dubai or Singapore, with the "made in" labels changed. The restrictions add additional transport costs to trade. A lot of wasteful expenditure and effort is being undertaken on both sides to prevent this trade. Other difficulties that hamper trade are the lack of transport facilities, warehouses, banking services, insurance, etc. The removal of barriers, reduction in tariffs, improvement of facilities and trade in services are needed for progress to be made on this front.

As people grow richer, cost is not the only basis for imports. Variety provides an important reason for trade. Greater trade between India and Pakistan will result in greater variety, such as in mangoes, textiles and spices. Consequently, an increase in India-Pakistan trade will not necessarily lead to competition on the basis of costs and destruction of industry and employment. Instead, customers will gain from the increase in the varieties they have access to. The response to the clothes and fabric from Pakistan in the last trade fair in Delhi indicated the interest of consumers.

At the same time, in another move forward, India has allowed FDI from Pakistan. A large part of global trade takes place within firms. Intra-firm trade can happen when companies span both countries. This would not only create avenues for greater trade, but also create the stakes for peace as more and more businesses have assets across the border. India should grant the equivalent of MFN status in FDI investment to Pakistan. In other words, it should treat FDI from Pakistan at par with investment from other countries such as Singapore, to which the most liberal investment regime is offered.

To monitor and ensure that the government's commitments translate into progress on the ground, the prime minister should set up a committee with representation from the private sector, government and independent experts. It must assess the implementation of the measures the government announces to improve economic relations with Pakistan. It should identify the difficulties that exist and propose changes to policy and implementation. The operationalisation of the MFN status to India will likely lead to an increase in trade. Both governments will need to identify the problems and work to solve them. Trade disputes that arise will need to be solved while trade facilitation will need to be increased.

In the case of India-Pakistan trade relations, even beyond the obvious economic interests, it is in India's strategic interest to increase economic cooperation between the two countries if it contributes to bringing prosperity to Pakistan. Then, India will have a neighbourhood with less poverty, less illiteracy and less unemployment and their negative social fallout.

In other words, better economic relations between India and Pakistan will not only bring economic prosperity, as is usually the objective of trade liberalisation, but it will also build greater stakes for peace and lobbies that are interested in continuing the businesses they have set up that depend on good relations between the two neighbours. This will create a deterrence to conflict.

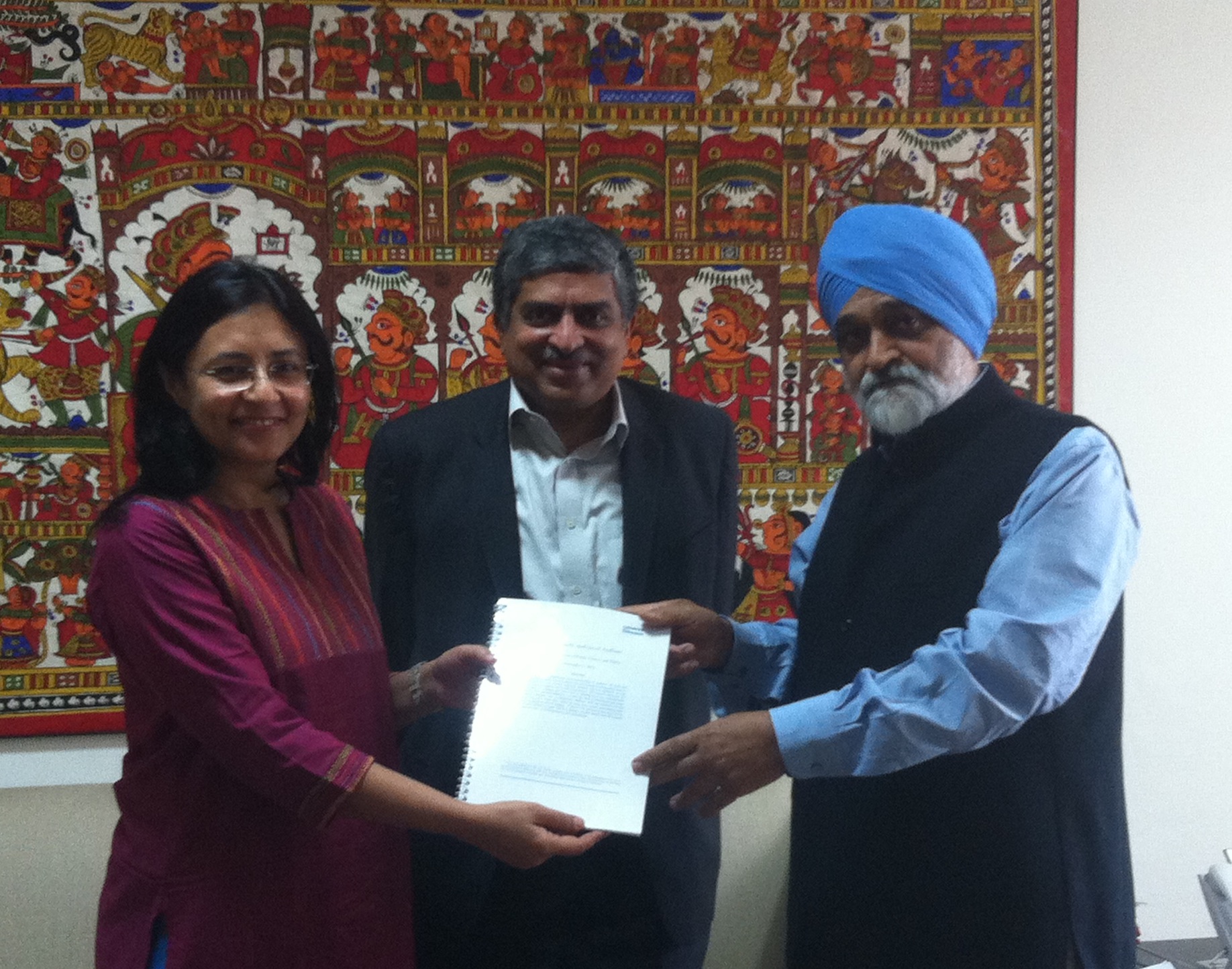

The National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP) released a study on a cost-benefit analysis of the Aadhaar programme, showing that Aadhaar can plug problems ofleakages and yield very high returns to the government.

The National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP) released a study on a cost-benefit analysis of the Aadhaar programme, showing that Aadhaar can plug problems ofleakages and yield very high returns to the government.